Alfred Felton’s bequest to the National Gallery of Victoria will always be the stuff of legend. His motivation for this munificence, which has enabled the purchase of 15,000 art works since 1904, has never been established. Could a chance meeting in 1892 with the Gallery’s newly appointed director, a young Englishman called Bernard Hall, perhaps supply the answer to a question that has teased historians for the better part of a century?

On the basis of twentieth-century histories, this may seem unlikely. A skilled artist best known for his nude studies, Hall was, according to accounts, intensely conservative and obsessed with the proposition that he and he alone knew what was best for ‘his’ Gallery and its students. These traits, it has been argued, were not only responsible for the perseverance of an unduly traditionalist ethos within the institution, but played a major part in the conflict that plagued its purchasing program. Described over time as a man of few friends but many enemies, respected but not liked by his students, aloof yet outspoken and lacking in humour or tact, Hall has entered the pages of Australian histories as little more than a bleak counterpoint to the sunnier rhythms that celebrate the heroes of the Heidelberg School.

For too long, however, this daunting mythology has obscured the true story of a man whose contribution to the art and social life of the developing community was immeasurable. Fortunately an extensive archive has enabled a more considered evaluation. Hall’s diaries bear witness to the selflessness of a life devoted to the Gallery, often at the expense of his own work, but also reveal the importance he accorded his family, a large and wide-ranging circle of friends and the Melbourne community at large. Letters from artists who had been his students confirm that he was widely esteemed as a teacher and that many young artists benefited from his support and friendship, particularly the women who may otherwise have been excluded from the professional status enjoyed by their male colleagues. The minutes of the Gallery Trustees hint at the diplomacy he could and frequently did exercise to ensure that crises were averted, business was enacted as smoothly as possible and growth was continuous. Even more significantly, in this context at least, the records of the Gallery chart several important gifts other than Felton’s bequest, each initiated or expanded as a direct result of Hall’s friendship with the philanthropist concerned.

The important lesson in all of this is that while published histories are often accepted without question, their imperfections should never be disregarded, and the critical importance of primary sources should never be forgotten. Although it may be difficult to see the Bernard Hall of legend as the inspiration behind the Felton Bequest, the man who emerges from the documents of his own time and place is a very likely contender indeed.

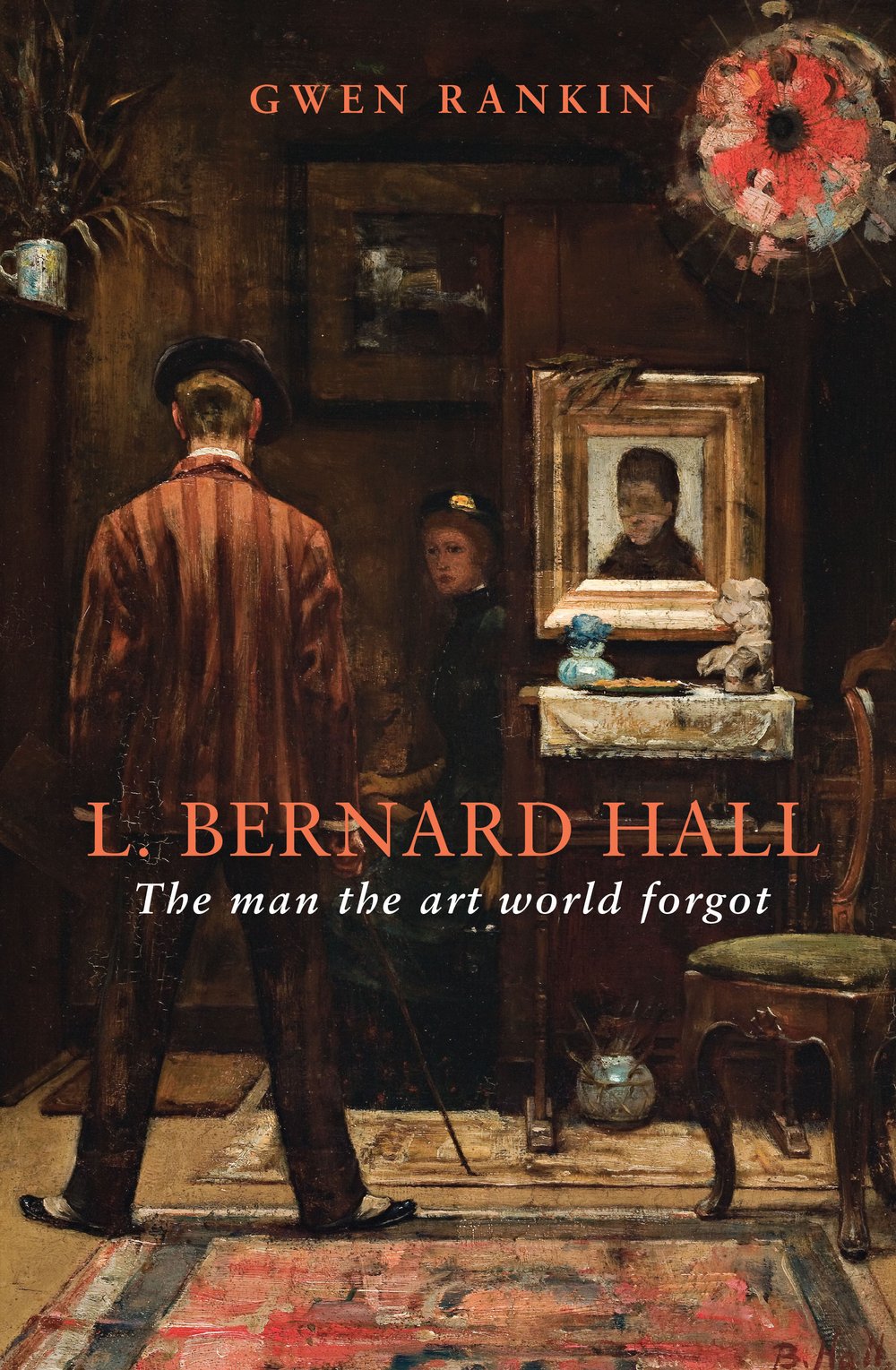

Gwen Rankin is the author of L. Bernard Hall: The man the art world forgot, released this month.