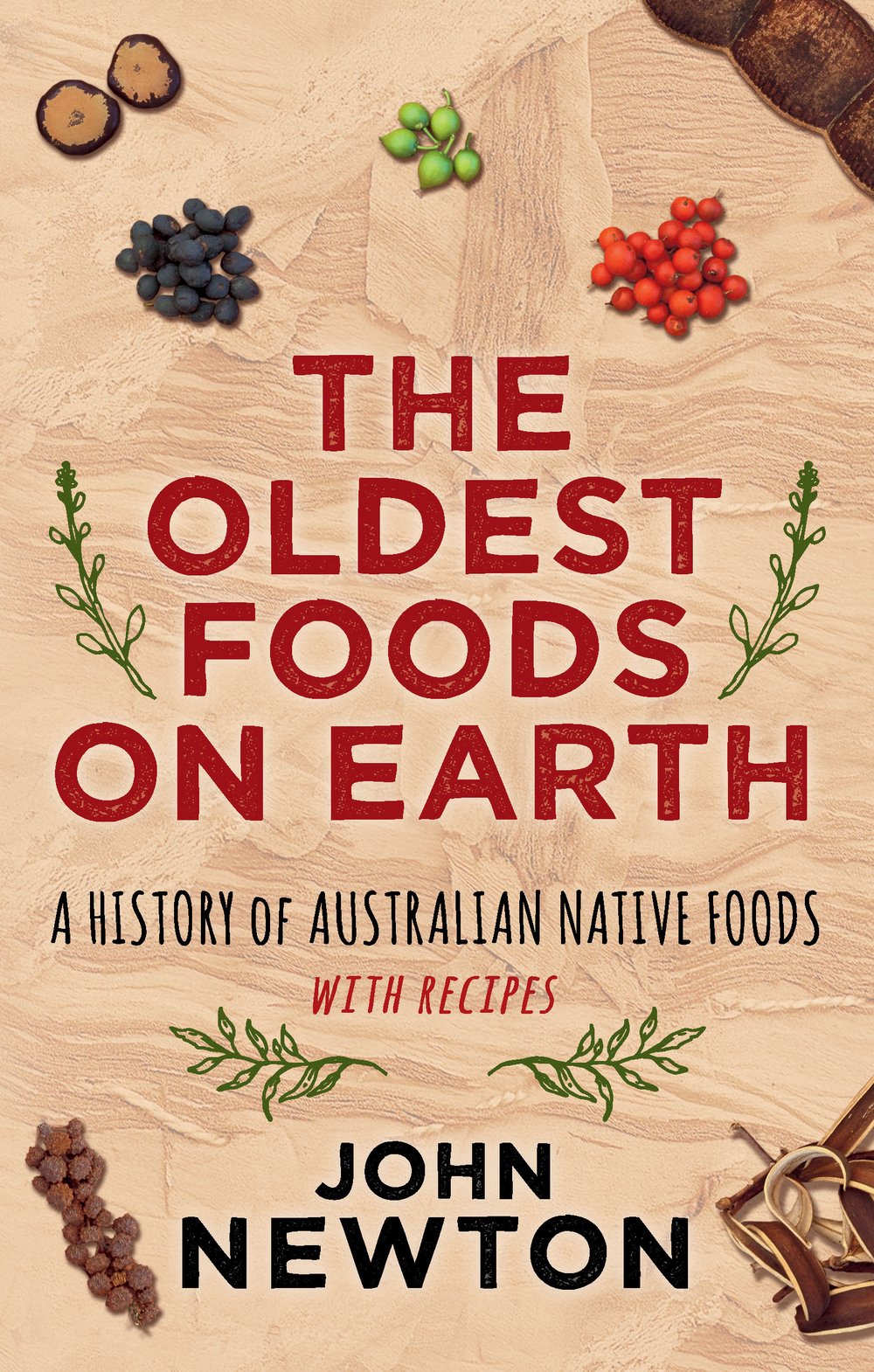

European Australians often don't stop to think about the foods that have grown in Australia for thousands and thousands of years. And when Indigenous people were removed from their traditional foods along with their lands, it was a complete cultural and nutritional disaster. John Newton’s new book The Oldest Foods on Earth reminds us of the impact.

In 1991, while preparing a speech, I rang the history department of a large university and asked to be connected to someone who worked on the history of food. There was a pause, and the person who answered replied with a question: ‘And what, might I ask, has food got to do with history?’

This was, admittedly, even at that time, a somewhat antediluvian answer, but it does reflect the academic attitude towards food in history until relatively recently.

Seven years later, Tim Rowse published his book White Flour, White Power: From Rations to Citizenship in Central Australia, which makes a clear and powerful connection between food and history – in this case, the history of Australia. ‘From the 1890s’, wrote Rowse, ‘rationing began to replace violence as a mode of government’. The overt violence could not be allowed to continue, because it seemed to be having no effect on the behaviour of the Indigenous people, often simply making them more belligerent. But rationing inflicted another kind of violence on the Indigenous people – one that is often overlooked.

The arrival of Europeans in 1788, with their own foods and livestock, and a way of farming entirely alien to this country, began the process of removing the Indigenous people from their traditional diet. Not only did European Australians ignore the foods that grew here, they actively discouraged the hunting and collecting of traditional food. The authorities considered such practices primitive and undisciplined, and believed they had no place in the process of ‘advancing’ Aboriginal society.

At first, rations were given to Indigenous people to supplement native foods. Then, as settlement increasingly denied Aboriginal people access to food and water, they began to develop tastes for beef, flour, sugar, tea and tobacco, and, as anthropologist Annette Hamilton writes, ‘the comfort of a blanket, the luxury of soap’. But in many outback areas, the official rations were inferior in quality and insufficient in quantity. They were just enough to encourage Aborigines to stay near the ration depot, but not enough to give them one square meal a day.

The cultural results of this forced change can be seen to this day. Removed from the land and a diet of nutritionally rich wild foods – and the exercise associated with hunting, fishing and gathering them – their health deteriorated rapidly and their numbers dwindled.

The Indigenous diet came to consist, typically, of white flour, white sugar, camp pie, salt and beer – unfamiliar, nutritionally incomplete food. It was a health disaster that has contributed to Indigenous populations having three times the average incidence of diabetes, twice the average incidence of heart disease, and six times the level of renal (kidney) disease as European Australians.

Examining what people eat, why they eat it and how they eat it is a critically important way to gain insights into history. And I hope my book demonstrates this from beginning to end.

* * *

The Oldest Foods on Earthwas published by NewSouth in February 2016. This article originally appeared on John Newton’s blog (https://eatourwords.wordpress.com).